Після п'яти років наукова революція в Україні кульгає (Ukraine’s science revolution stumbles five years on)

Журнал Nature в статті під назвою "Після п'яти років наукова революція в Україні кульгає" описує актуальний стан української науки:

"Ukraine’s science system is in a precarious state, despite promised improvements in the wake of a revої olution five years ago that aligned the country with the European Union.

National science spending remains low, government funding is used inefficiently and low salaries discourage talented students from embarking on research careers in the country.

“We’ve been promised change for years,” says Nataliya Shulga, chief executive of the Ukrainian Science Club, a science-advocacy group in Kiev. “But what’s happened so far is an imitation of change, rather than genuine reform.”

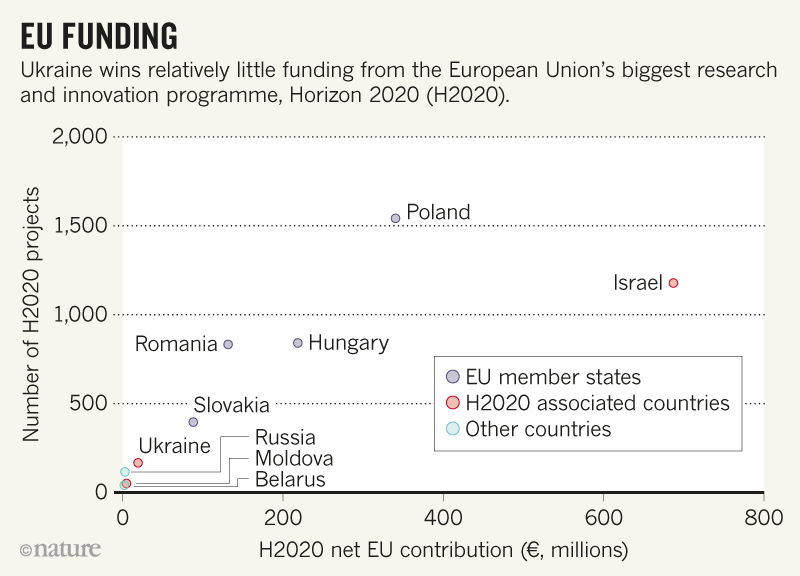

The ‘Euromaidan’ revolution, also known as the Revolution of Dignity, was sparked by a wave of protests and civil unrest that, in February 2014, culminated in a change in leadership. It severed Ukraine’s ties with Russia and prompted the election of a pro-European government, raising hopes among scientists that Western partnerships would form and steer them out of international isolation (see ‘Awaiting a science revolution’). The initial aftermath was promising: the new government promised to revamp the country’s obsolete, Soviet-style science system, and to boost research and development expenditure. In 2015, Ukraine started participating in EU research programmes as an associated country, giving it the same rights as member states when applying for EU grants. And in early 2016, its parliament passed a law to strengthen science, technology and innovation.

But those early efforts haven’t substantially improved things, say scientists. Government spending on science declined to a historically low 0.16% of gross domestic product in 2016, and has not increased much since.

Scarce money

The little public money that there is goes largely to research institutes operated by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU) — the country’s main basic-research organization — many of which are outdated. The academy will receive nearly 5 billion hryvnia (US$183 million) from the government in 2019 — almost twice what it received in 2016.

But Shulga says that even this relatively generous pot will not be enough for the academy’s institutes to buy modern research instruments, such as electron microscopes and spectrometry machines, without foreign aid. This in turn limits Ukrainian scientists’ ability to compete with researchers in richer countries.

Patience is wearing thin, in particular among the country’s young scientists, who can barely get by on their scant salaries. PhD students in Ukraine get between 3,000 and 4,800 hryvnia a month, and even experienced researchers rarely earn more than 13,500 hryvnia per month.

Ukraine “deserves a science system worthy of a developed country”, says Yulia Bezvershenko, a physicist at the Bogolyubov Institute for Theoretical Physics in Kiev and a co-chair of the NASU’s Council of Young Scientists....." Pdf version

Copyright © із видання: Nature 566, 162-163 (2019)